One of the lovely things about playing a simulationist game system is that it almost always has a bibliography at the end. In the scientific world, bibliographic references in a journal article provide a sense of communal teleology; that is, it reminds the reader that the purpose of a particular paper isn't to be impressive in itself, but to participate in a conversation that helps to meet the ends of everyone involved in that field of research. Playing

Korea: The Forgotten War helped me to understand politics during the Truman/Eisenhower era, clarified why we maintain a presence in Korea today, and gave me a better perspective on what was going on in those old MASH episodes. And of course, reading books and watching movies set in a particular fictitious universe creates a heighten level of engagement with the narrative elements of the game as well.

|

| This little guy is my totem animal, I think. |

When I was young, I had a small collection of Safari Cards, which were a mail-order product that functioned as a nerdier counterpart to sports cards. Each card had an animal name and picture on the front, and a back full of information about that creature's ecology and taxonomy. The cards were satisfying in the way of any collectible item, but also had a reassuringly authoritative voice: "This is science! Collect science!"The abstracted icons for class/order, the stylized terrain, the color-coded Mercator map, all of these suggested elements of some systematized universe of adulthood that was deeply inviting to me. I wanted to go out into nature, discover real life beasts to match each picture, and put a little check mark next to a list of the cards in my collection. That impulse has never really gone away, and probably explains why we own a set of National Park refrigerator magnets and topographic maps.

I wish I still had my set (or a larger, more comprehensive version of it), just so I could build a game around it. The basic mechanics of traveling around to collect elusive critters already had its CCG heyday in the Pokemon era, but the stylistic aspects of that genre was sadly antithetical to the Safari Card ethos. Instead of feeling dryly analytical, like something from an old European library, the games of the 90s were garish pastel affairs, light on text and far from the gritty feel of wrinkled lizards clutching grimy rocks. The best approximation to Safari Cards might have been the endless series of "The Ecology of the ______" articles in Dragon Magazine that ran during the early 80s as an expression of

Gygaxian naturalism, and were condensed into increasingly detailed expansions to the 1e Monster Manual.

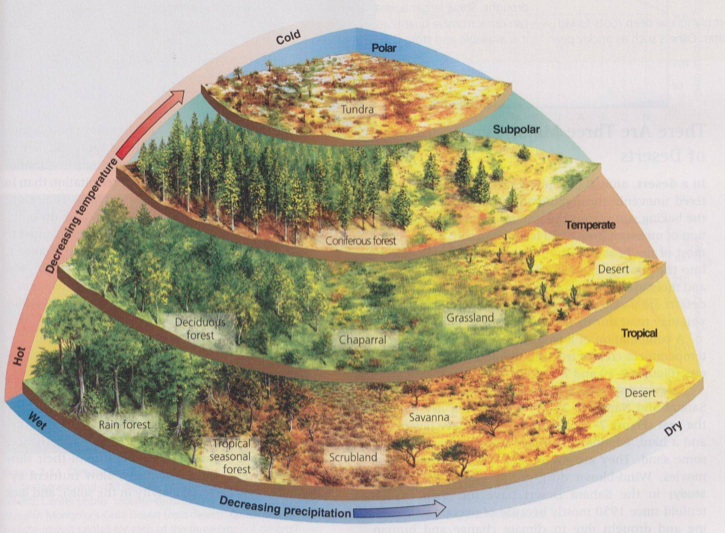

The same thing is true of a variety of numerous books about geography and climate that I read during the late 70s, laid out with textbook figures that merged art and data. Here's biome chart that could easily have been plucked from one of the pseudo-textbooks in my childhood collection:

This picture just begs me to create a small table where rolling dice select the level of precipitation in a hex map zone, and cross-referencing the latitude zone on a global world map indicates the type of terrain it contains. It's a simplified version of a messier reality, to be sure, but it feels scientific. And once nourished on this kind of intellectual fare, it's hard to accept anything that doesn't clear the same bar for rigor and consistency.

This is, if you will, part of my design bibliography. My "

Appendix N", an RPG player might say. The game it would create would be the same sort of game that appeals to someone who wants to collect detailed ecological data for hundreds of Safari Card species, an overwhelming deluge of academic detail and digressive flavor-text. It isn't one which the current industry standards support, with the greater emphasis (post Euro-game revolution) on abstracted and anti-simulationist design. But it has a powerful nostalgic draw for me.

I like the idea of rolling precipitation for each hex. Perhaps the result should be modified such that previously explored adjacent tiles are factored into the outcome. Thus the change of climate is more gradual, and perhaps less abrupt or patchwork.

ReplyDelete