Runebound

Number of Players: 1-4 (best with 1-2)Year Released: 2004

Rule Book: 12 pages (in 3 column format)

Playing Time: 240 minutes

Mechanics: 1d20, roll-high, modify roll (changed to 2d10 for 2nd edition)

Rating: 7 out of 10

Description:

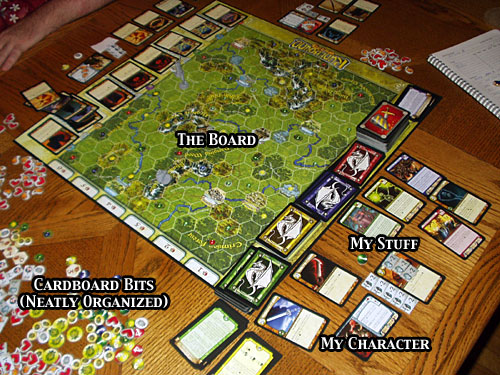

Runebound is a fantasy game with a theme inspired by modern role-playing games. Each player controls a single hero who wanders around a fixed board, slaying randomly generated monsters and accumulating treasures and allies. Exploration aspects of the game are minimal, and most rules relate to simulating combat. The game objective is to defeat a powerful dragon, either in battle or by collecting a specific set of items. A more detailed descriptive review may be found here.

Player Agency:

Runebound uses a movement system based on terrain, rolling a specified number of dice (4 to 5) in order to determine which types of terrain are possible to move through. This creates a puzzle component to movement, as each die face allows access to only certain types of terrain. Rare types of terrain result, like swamp, are less accessible. This creates the odd situation of standing right next to a hex and being unable to enter it, yet being able to run a long distance in a different direction. There are still usually a large number of options available, especially early in the game.

Combat is highly random (especially with 1d20 in the first edition), and there are few decisions to be made. Typically most characters have a choice between attacking with their "best" style of attack (mind, body, or spirit), or else making the earliest possible attack even if it might be weaker. This introduces some amount of tactical complexity. As extra allies are accumulated, the game acquires an element of resource management, with a frequent decision of whether to use powerful allies at the risk of losing them, or to hold them in reserve.

For the most part, each random event or encounter has a fixed outcome that can't be resolved in multiple ways. The wilderness always contains hostile enemies, and the villages always contain friendly allies and merchants.

Emergent Complexity:

Early in the game, each player has only a single character. As allies are gained, there are more choices to be made about how to use them. Otherwise, the game primarily gives harder versions of older enemies with improved attribute scores. In particular, encounters continue to involve only a single enemy at one time (sometimes glossed as a group in the description text), even as the hero gains new allies. The 2nd edition resolves this asymmetry by limiting the number of allies (or, as a variant, charging maintenance for them), but this reduces the emergence of complexity.

Most subsequent games follow the same pattern, with little variation between play sessions. Certain items can influence strategy, but there's really only one path to victory: the accumulation of greater battle prowess through experience, items, and allies. Distinct hero specializations (mind/body/spirit) result in mechanically identical implementations, and feel mostly cosmetic rather than altering strategy. This is characteristic of a modern game that avoids mechanical diversity at all costs. In that sense, this game is very much like an MMO (where physical and magical combat work about the same way) than a classic pen-and-paper RPG (where the magic system looks radically different from other play elements).

Verisimilitude:

The art style and naming conventions suggest a game intended to emulate comic book, action-oriented fantasy tropes. Heroes are slightly ridiculous, encouraging a lightly humorous approach. Virtually all mechanics are intended to present a world of heroic deeds, with no need to both about mundane items or practical exploration complications (like finding food or getting lost). The game does a good job of matching theme to mechanics, although the choice of theme itself might be criticized as being a bit too juvenile for "serious" gamers.

Certain aspects of the game seem to suggest theme elements that are never developed. For example, the dice system might represent the effect of getting lost and giving up to strike out in a different direction, and the process of getting "knocked out" in a battle and returning to a village might represent being the beneficiary of either a ransom or a rescue mission. The game booklet seems mostly disinterested in this kind of simulationist detail, electing instead to simply present arbitrary rules without comment.

Verdict:

This is a basic but high-quality thematic game. The development of the theme is consistent, if a bit cartoonish in flavor, and there are enough decisions to keep the player engaged. The level of rules complexity is appropriate for a short game with the need for limited introduction, but insufficient to create multiple paths to victory. Overall I regard this game as a bit too simplistic for heavy play, but it feels about right for an entry-quality game to the genre.

Somewhat problematically, it plays best with either 2 players or as a solo game due to the extended downtime between player turns. Yet the complexity level of the game rule booklet suggests it's intended mostly for a group or club that rotates between different games from week to week, as a lowest-common-denominator experience that won't intimidate inexperienced players. This is a persistent problem with RPG-clone boardgames which intentionally emulate a cooperative "player-versus-environment" style of play.

One of the best features of this game is the ability to leave a challenge encounter waiting on the board and return to it later. This creates some meaningful strategy choices, as assembling the correct combination of allies and items for a given opponent can involve careful planning. The movement system, however, encourages more of a random wanderer feel, rather than careful planning of a sequence of multiple turns. This sort of tension between design objectives and mechanics prevents this game from being as strong an experience as it might otherwise be.

No comments:

Post a Comment