|

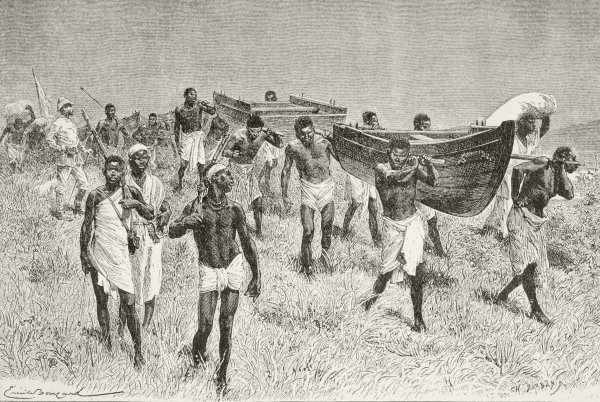

| Henry Morgan Stanley: Traveling in style |

One of my objectives in designing my own game was to insure that size itself was reasonably represented as a scalable aspect of expedition design. That is, it should be possible to send a small, peaceful force of diplomats or a huge army of mercenaries, and both approaches should have advantages or disadvantages. But the route of conquest should definitely involve trending toward the larger end of that sliding scale, and trying to squeeze a real-world military expedition into the confines of the tradition six-person RPG party just doesn't feel consistent to me.

For sake of reference, I looked up a number of famous expeditions and their approximate number of members. In some cases, the data for support personnel like porters were omitted, and would have swelled the ranks even further. It's interesting to see how the function of an expedition (conquest, trade, or survey/discovery) influences the personnel required. For sake of comparison, I've also included a couple fantasy questing expeditions from Tolkien's novels and from mythology.

- Hernando Cortes, Mexico (conquest): 550 Spaniards, 3000+ natives

- Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, New Mexico (conquest): 400 Europeans, 2000+ natives

- Hernando de Soto, Mississippi River Basin (conquest): 700

- Burton and Speke, Nile Basin (survey/discovery): ~200

- Francisco Pizzaro, Peru (conquest): 178

- John Fremont and Kit Carson, Oregon Trail (survey/discovery): 55

- Jason and the Argonauts, Search for the Golden Fleece (quest): 50

- Lewis and Clark (Corps of Discovery), American West (survey/discovery): 33

- La Salle Expeditions, American Midwest (trade): ~20

- Burke and Wills, Australian Outback (survey/discovery): 19

- Thorin and Company, Erebor (quest): 14

- Fellowship of the Ring, Mordor (quest): 10 (including Gollum!)

Fantasy quests are something of a different situation, since at least in the original narrative template designed by Tolkien, they are oriented toward infiltration and secrecy. Thorin wants to avoid detection by Smaug, or the elves of Mirkwood. Elrond and Gandalf want to slip the Ring into Morder without attracting attention. But it's decidedly odd (and probably a reflection of Tolkien's long shadow) that this style of expedition is now the default for virtually any game that involves heroic exploration. In effect, computer games like E:C are imitating RPGs, and RPGs are imitating Tolkien, without much contact with history along the way.

Early RPG players evolved out of the wargaming community, which originally respected much larger groups. The initial release of D&D in the 70s, for example, suggests as a guideline for size: "Number of Players: At least one referee and from four to fifty players can be handled in any single campaign, but the referee to player ratio should be about 1:20 or thereabouts." (Men and Magic, Vol I.) Bear in mind that this was at a time where each player might control not just a single character, but a small squad of henchmen and mercenaries; many early game mechanics (like the charisma tables) were explicitly designed to represent the player character as a commander of troops and a diplomatic spokesperson, not a solo hero.

I think it's fair to say that a realistic simulation of the age of exploration and discovery (roughly, the 16th through the 19th centuries) would need to be able to scale comfortably up to an expedition size of 1000. Of course, there's a satisfaction in being able to start small, with a few scouts, and only later grow into the end-game of a small conquering army steamrolling across a map of natives. But the combat system, in particular, needs to be workable on a grand scale in order to reproduce anything like the fall of Tenochtitlan.

No comments:

Post a Comment